17 years ago in November, Maximillian Büsser arrived on our shores armed with just two sketches of watches that were unlike anything the world had ever seen, and enough charm to convince Michael Tay, Group Managing Director of The Hour Glass, to place an order that would take two years to fulfil.

Photo credit: Sotheby's

Photo credit: Sotheby's

We now know that one of those designs was realised as the HM1, the audacious figure eight-shaped timepiece that set Büsser’s brand on a trajectory of horological weirdness.

But Büsser’s crazy ideas have always been backed with the mechanical ingenuity provided by his many collaborators and now, with the first MB&F Lab open in Singapore, the launch of the brand’s first book, MB&F — The First Fifteen Years, and 20 original movements under his belt, Büsser is ready to reflect on his road to become one of the most memorable rebels of the industry.

Related

World's First MB&F Lab in Singapore

Located at the iconic Raffles Hotel on the ground floor of the Raffles Hotel Arcade, the boutique is the first of its kind for the new MB&F Lab Concept, which is soon to open next in Paris and Los Angeles.: Read Story

Publisher’s Note

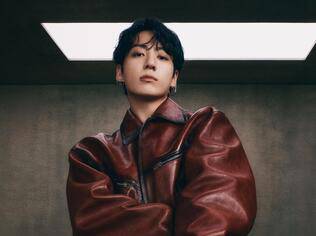

Personifying the brand's motto "A creative adult is a child who survived," Max has enjoyed endearing success due to his ability to maintain the boundless imagination of a child, unconstrained by the burdens and trappings of adulthood.

Here at SENATUS, we affectionately call him the Peter Pan of horology.

SENATUS: It’s been quite a journey, and you have a lot to celebrate this year. Was this what you had envisioned for the brand when you started?

I could not have imagined one bit of this. When I created the brand I only had the designs for the HM1 and the HM2 that never came to be. But suddenly we have all these milestones. People think I’m a visionary but I’m not. I just wanted to create the HM1 and become an entrepreneur. If I was told 17 years ago that this is where I would end up, I would say, “Take my blood. I’ll do it.” But I was totally clueless as to what that entailed.

It couldn’t have been easy, getting to where you are today.

There were brutal years. 2007, 2009, 2012 and 2014 were the years we came close to bankruptcy.

How did you push through?

I think I was very, very optimistic. When I created MB&F there was a very clear possibility that I would fail because I didn’t have, by far, enough money. But I had to try. I came from no money, so even though I made a lot of it at Harry Winston, I wasn’t afraid of going back to zero. If I failed, I failed. So I got over those four horrible years by working like hell, but there were people who helped me.

How did they help?

In 2007, my main movement supplier got sold to another brand overnight. Of course, that brand didn’t want to create movements for third parties, which I can understand, but for the first and only time in my life I grovelled. I told the new owner that if he didn’t assemble my movements I would be dead.

But by an insane chance, Peter Speake (of Speake-Marin watches) was also there that day for his own personal business. After he watched me grovel for about five minutes he took my arm and said to me — in English — “We will deal with it”. Later in the car, he started calling up all his independent watchmaker friends, telling them them his friend Max was in trouble. All of them went, “Who’s Max? No, I don’t have time for this.” But Peter said they owed him, and so these guys turned up — begrudgingly — to try and assemble our first movements.

Everyone thought we were crazy because there were missing parts and no assembly plans. It was like trying to put together a jigsaw puzzle without knowing what the end picture is. What normally would have taken two weeks took them five months because there were some badly made components and construction issues. I was going completely bonkers.

But what’s incredible is that amongst these five watchmakers who I had never heard of before at that time was Stephen McDonnell, the one who would go on to create our Legacy Machine Perpetual and Legacy Machine Sequential EVO. From that horrible event I met a genius who would eventually give me 10 years of his life to develop these world-premiere calibres.

Some would say that’s destiny.

I don’t believe in god, but I believe in karma. Most of these people were people I didn’t help, but they helped me. So that’s what I’ve been trying to do over the last decade. The MB&F Labs and M.A.D Galleries help artists because when I met them, they could barely make ends meet.

These collaborations have resulted in a beautiful, symbiotic relationship that promotes both mechanical art and watchmaking. How are you dealing with the explosive success of your brand?

In 2013 we decided that the brand wouldn’t grow, and we stayed at more or less the same quantity between then and 2021. But if we stayed at that level of production we would have 10- to 18-year-long waiting lists. So last year we crafted 278 watches, and we’re trying to make 350 this year, and maybe 420 pieces the year after. But it’s still a drop in the ocean compared to the demand out there.

Higher demand doesn’t sound like a bad thing. Why the reluctance?

Growing means having to find the right people. I’ve only hired two people a year for the last 10 years, but I had to hire 10 people in the last six months. It’s not about finding competent people, but people with the right attitude. It’s been 17 years but we still feel like a startup. Everybody has a purpose, feels engaged, and is inspired. It’s super dangerous if I bring in someone without the right mindset. That’s what’s been keeping me up at night.

You didn’t want the company to expand, and but you did what you had to do. In what other ways have you surprised yourself on this journey?

I said I would never do a round watch, but there were a lot of things I said back then that I look at now and think to myself, “Shut up. Just shut up.” I am incredibly fond of the HM1, but sometimes I shake my head and wonder how I actually created that, because I would never make something like that today. It was mind-blowing and novel and insane for the man I was in 2003, but now when I look at it, 20 calibres later, I shrug go, “Yeah, okay.”

You’ve grown along with your brand.

This journey isn’t just about me becoming the creator I am today, but also who I am as a person. I was a socially awkward youngster with no friends. I was a complete dork.

Anyone who’s met you would find that hard to believe. How did you turn that around?

Two things happened. I got my first job in watchmaking at Jaeger-LeCoultre when they were still small so I found my family there. Then-CEO Henry-John Belmont took me under his wing and he gave us all a purpose: to save a company that was going bankrupt. I realised I was pretty good at my job, and went and did the same for Harry Winston. It was never about the money; my whole professional life has been about saving something. My confidence grew as a result.

I also owe so much to the women who loved me before I was “the cool guy behind the brands”, my mother included.

I think you need love to build yourself up. It’s difficult to love yourself if you’ve never felt it.